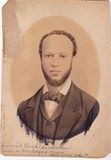

Jeremiah Burke Sanderson (1821-75), a native of New Bedford, learned to agitate for equal rights in his hometown and became one of the most active proponents of the cause in early California.

His ethnic origin is not entirely clear. His father, Daniel, may have been partly or entirely Scottish; his mother, Sarah, was either entirely or partly native Wampanoag Indian. The Sanderson family came to New Bedford from Bristol, Rhode Island, about 1826-27; Daniel Sanderson appears to have left the village after 1830 and never returned.

Before Jeremiah Sanderson turned twenty, he had become active in abolitionism. In 1840 he was elected secretary of a New Bedford colored citizens’ meeting in support of the “old,” Garrisonian American Anti-Slavery Society and had begun his lifelong correspondence and friendship with Boston abolitionist William C. Nell. By June 1841, when he was working as a barber in downtown New Bedford, Sanderson became local subscription agent for Garrison’s Liberator. On Nantucket, in August that year he spoke at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society meeting that catapulted Frederick Douglass to national notice. Both Parker Pillsbury and Edmund Quincy had high praise for Sanderson’s Nantucket address. The New Bedford native spoke often at antislavery and equal rights meetings throughout his life. In the course of his antislavery work Sanderson developed close relationships with Frederick Douglass, with whom he lived while the Douglass family resided in Lynn, Massachusetts, and the fugitive-turned-antislavery orator William Wells Brown. Sanderson was a featured lecturer at the annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1845. He was one of two Massachusetts delegates to the 1853 National Convention of the Colored People of the United States, and a member of the State Council of Colored People of Massachusetts in 1854.

Sanderson resigned the last-named position later in 1854 before moving to California, clearly to improve his financial position. He married in about 1848 and had a wife and four children to support by 1855. As he wrote his wife from California in 1857, “I have always hoped, and do hope to do something better for my family here, than I can at home.” In 1856 Sanderson established Sacramento’s first school for children of color and ran it without any state aid for more than a year. During that time he tried to persuade the state to support public education for the students he taught and those his school was unable to accommodate. He was also active in the first and subsequent conventions for people of color in that state. Jeremiah Sanderson’s family joined him in California after the death of his wife’s mother, Mary Gibson, in March 1859. Their daughter Mary Sanderson Grasses later became the first black public school teacher in Oakland, California.

In 1859 Sanderson was placed in charge of San Francisco’s first black public school and named its principal in 1864. By 1868 he was teaching school in Stockton and in 1871 was appointed vice president of a convention held there on the education of children of color in the state. He remained active in equal rights, having helped found the state’s Franchise League in 1862 and having signed a call in 1873 for a state convention of blacks to assure equal rights under the Fifteenth Amendment. During this time he also helped organized the California Conference of the Union Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, served as a local preacher, and was ordained an elder in the church by T. M. D. Ward, who had also lived for a time in New Bedford, in Stockton in 1871. Sanderson died tragically four years later: returning home from a prayer meeting at his then current pastorate, Shiloh AME Church in Oakland, he was struck by a Southern Pacific train as he crossed the tracks and killed instantly.