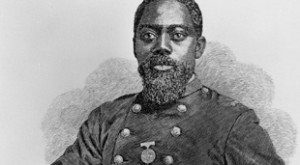

For his outstanding bravery in holding the flag aloft in the heat of the terrific fight, and bringing it safely into camp, Sergeant William H. Carney was awarded the coveted Congressional Medal of Honor, becoming the first African American to receive this honor.

William H. Carney was born in Norfolk, Virginia on February 29, 1840. His father was William Carney who had doubtlessly adopted the last name of his master, Major Carney, owner of a large plantation. His mother’s name before her marriage was Ann Dean. She too, was the property of Major carney. At his death, Ann and all of the other slaves on the Carney plantation received their freedom.

Young Carney was a bright, ambitious lad and his mother and father realized the importance of receiving some type of education for their son. In spite of the fact that it was against the law to teach Blacks to read and write, the Carney’s sent their son to a secret, private school in Norfolk, Virginia. William was an apt scholar and readily absorbed a well-rounded education. After the family gained their freedom, the father saved every penny that he possibly could with the view of moving from Virginia to places farther north where his family would be far from the suffocating, inhumane grasp of slavery and the slave-catchers.

The elder Carney took his little family first to Pennsylvania, but decided not to make his home there. He next moved to busy New York City. This too, he did not find to his liking. Bounty hunters or slave catchers were numerous in New York and even freeborn Blacks were often kidnapped and sold into slavery. He wanted a quiet, peaceful, freedom-loving place where he could bring up his son insecurity and dignity. Hence, like Frederick Douglass, he journeyed to the city of New Bedford.

Here, in the city of New Bedford, is where young Carney spent the greater part of the remainder of his life. He did odd jobs, worked in various stores of the city, and won the respect and love of both white and black associates. He continued his interest in the church. Often he attended the Bethel A.M.E. Church where he loved to sing and listen to the older men plan the escape of slaves from the south. However, the church of his choice was the Union Baptist, which was organized by Rev. William Jackson.

About this time, Carney entertained strong ideas of making the ministry his life career, but then came the Civil War and Carney felt he could best serve his God by serving and his oppressed and enslaved black brothers. On March 4, 1863, Carney, along with forty other blacks from New Bedford enrolled in Company C of the Massachusetts 54th to take part in the Civil War. The Massachusetts 54th Regiment was the first black army unit to be raised in the Northern States. After only three months of training at Readville, Massachusetts, they were shipped to the main theater of the war, South CArolina. Here, they saw action at Hilton Head, St.Simon’s Island, Darien, James Island and at Fort Wagner.

On July 18, 1863, these brave black soldiers led the charge and attack on Fort Wagner. During the heat of the battle the color guard, John Wall, was struck by a fatal bullet. He staggered and was about to drop the flag. Carney saw him; he threw down his gun, seized the flag and held it high throughout that fierce and bloody battle. Though twice wounded in his leg and right arm, bleeding, and hardly able to crawl, Carney clutched that flag until he finally reached the parapets of Fort Wagner. There in the sand, he planted Old Glory, still staunchly clutching it until he was rescued alost lifeless from loss of blood. Carney still refused to give up the flag to his rescuers but grasped it even tighter. Then he crawled on one knee, assisted by his comrades until he reached the Union temporary barracks. Recognizing men of his own regiment, he cried: “The old flag never touched the ground, boys.”

From New Bedford Black Heritage Trail by Jane Waters