Mary J. “Polly” Johnson (1784-1871) was one of the preeminent abolitionists and confectioners in nineteenth-century New Bedford.

She was born in neighboring Fall River, Massachusetts, to Isaac and Ann Mingo and lived in New Bedford from the time of her second marriage in 1819 until her death. The home she shared with her husband Nathan (1797-1880) at 21 Seventh Street, now a National Historic Landmark, was the first home in freedom to renowned fugitive Frederick Douglass.

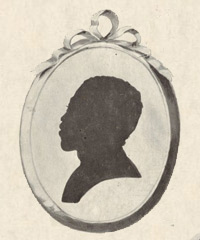

As a free woman of color, Polly Johnson was committed to assisting those in bondage. She often attended antislavery meetings with her husband, and she housed at least one other fugitive at 21 Seventh Street in addition to Douglass after her husband left New Bedford in 1849 during the California Gold Rush. New Bedford’s Daniel Ricketson recalled that Polly “was a fair mulatto, always lady-like and pleasant. I remember of seeing her walking arm in arm with Mrs. Maria Weston Chapman, down Summer street, Boston, after an anti-slavery meeting a short time before the war, while I had the honor of escorting the venerable Lucretia Mott.”

Much evidence suggests that Polly’s wages as a domestic in her early years in New Bedford went toward Nathan Johnson’s effort to amass the four properties he came to own on Seventh and Spring Streets. And her work and business sense are probably what made it possible for the couple to keep the heavily mortgaged properties in the 1850s, during Nathan’s time in the gold fields of the American West, and to build the Greek Revival-Italianate addition on their 21 Seventh Street home in 1857.

Polly Johnson is best known, however, as a candy and cake maker, while her husband was, among other things, a caterer. One local newspaper article stated in 1898 that she had learned “some of her art as a cook” in France and that “she was her husband’s chief assistant in making and serving delicacies and in preparing the table decorations.” In 1856 the city directory shows that she ran a confectionary and cake store at 23 Seventh Street (long since replaced) next door to her home. New Bedford’s Eliza Rodman wrote that when she went to Polly Johnson’s house one day in late April 1841, the woman was “preparing for a marriage” at the home of John Avery Parker, then well on his way to becoming New Bedford’s wealthiest citizen. In June of the same year Eliza “went to Polly Johnson’s to engage cake & ice cream” for an evening party she had planned.

In 1844 the abolitionist Caroline Weston, then teaching in New Bedford, tried to persuade her cousin, the antislavery orator Wendell Phillips, to speak in the city by promising that “Polly Johnson shall freeze her best ice & ice her best cakes” if he came. An account in the papers of whaling merchant Charles W. Morgan shows what he and his wife Sarah bought from Polly Johnson through the year 1836—candy, sponge and loaf cakes, “jumbles,” shortcake, ice cream (sometimes frozen in a fancy mold), fruit, macaroons, blanc mange (a kind of molded pudding), calves’ feet jelly, candied pears, and lemonade. In that year the Morgans bought more than thirty dollars’ worth of confectionary and cakes from Polly Johnson on forty-five separate occasions; molded ice cream was the most expensive thing they purchased, at two dollars’ each.

In her 1914 reminiscence New Bedford Fifty Years Ago, Maud Mendall Norton recalled “Polly Johnson’s candy shop on Seventh Street, with its toothsome ginger cookies, sticks of candy and spruce gum” as she knew it in her girlhood in the 1850s; in the shop Polly “hobbled about . . . exchanging the children’s pennies for Jackson-balls and John Brown’s bullets.” From documents such as these, New Bedford Historical Society is assembling an inventory of what Johnson offered in her confectionary shop. The Society plans to research these nineteenth-century recipes and ingredients with an eye cast tentatively toward reviving Polly Johnson’s confectionary in the city of New Bedford.